Thinkers

An Introduction to Samata concept & our Gurudev

Yet Samtavad would not, in actual fact does not, encourage us to look alike on these opposites constitutive of our mortal being as long as we remain mortals and fight a desperate fight against our inevitable and destined fate; a stern discipline we have to undergo before we can even think of samatā, sameness, not to speak of living it. For, not before dying unto himself can a man look alike on these dualities, the stuff our mortal life and being are made of. Mere theoretical deconstruction of these opposites will not do; he must live the uncertainty that he is as a [no-]being placed between these opposites, between the given condition and the transcendental urge in us, between the past and the present, between oneself and one’s other, between life and death. And to accept and live this his unhappy condition, he has to have the humility to become a mere passive witness of these ever recurring deadly tensions and conflicts within him, to stand apart from these as if these latter were mere events happening before him and not in him. He has to, in other words, cease to be a doer, accepting all the uncertainty that goes with his being as a mortal, as a creature uncertainly placed between the two poles of birth and death. But not before dying before his actual death can he have the patience, the patience all passive, to live his mortality and be his mortality, undoing thereby both birth and death and what lies between the two, his so called life.

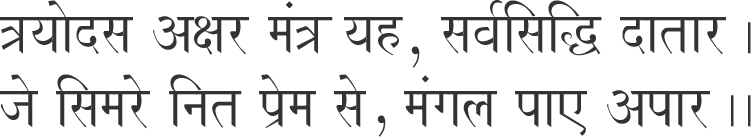

This patience would not come to man on its own, man has to burn his narcissistic self into this passivity, passivity that no tumult of life and no fear of death can ever disturb or disrupt. But the way to this patience the absolute is not the way smooth, hard it is and painful, of death-in-life is it the way. Man has to, as a first step, give up all his cunning and must become straight in his dealings of give and take, earning his daily fare through upright and honest means. When he comes to be honest and sympathetic, kind and empathetic, he has to take to the five regulative principles of Samtavad to prepare his way to the state where all turns one and the same, death no less than life, woe no less than weal. The five principles are the principles of simplicity, of truthfulness, of service unto others, of participating in the company of a sage, all open to the words that flow out of his lips, and lastly, there is the principle of simaran (smarana), remembrance of the Real.

Our simple fare, our plain wear and our plain word shift our attention from our narcissistic self to make it focussed on what is before us, other persons and things, even what we call inert and lifeless things. For, our love, when it flow out of our narcissistic confines, expands enough to spread out on the earth before us to rise above it up to the sky and to what lies beyond the sky, beyond all that we know and experience. Truthfulness kills all our cunning, dismantling all our defence mechanisms vis-a-vis others, mechanisms that make of us mere monadic beings, isolated, unrelated and frightened. It is truthfulness that transforms this narcissistic being into being the genuinely related, an authentic Mitsein, a being-with-others. And since this open being ever lives at the mercy of others, his all self-mechanisms dismantled, he cannot but find himself a being towards death, a being mortal, for the cruelty of those around him will not let him feel at home in the social world, will not let him find himself related. Alone he will become, a being alone related only to death, for that alone will be his refuge from the cruel wounds he will receive from others. This being towards death, this being the genuinely mortal, will then become a seeker of the truth, where all the wounds that we receive in our pilgrimage from birth to death may come to be healed. No secular knowledge can then enlighten this being, unhappy and desolate, and no power can make him feel secure, for all power will then seem to be invested in death, in that only. It is this unhappy man, simple and humble, open and truthful, but dying every moment, that will find all his possessions a torture and bondage and would gladly part with them in the service of the unhappy and distressed. But pain of mortality, that fear of the unknown, will possess him all the more, for negation, the ultimate end destined for him, that sheer negation, will deny him every consolation, every promise of release from his condition. So, he will seek a seer that has seen through death, seek him to know what death is, what its meaning is, and the meaning of our destiny as creatures of mortality and of pain the inconsolable.

To be in the presence of a seer the true is to be in the presence of the great mystery of life and the enigma that our death is. For, he seems to exceed all the defining bounds of humanity, humanity we are familiar with. His face is not the familiar face of man, it is an expression of the unknown and the unknowable, a riddle which neither death can encompass, nor life, nor the here nor the beyond. A stillness it is, a stillness which nothing can disrupt – neither man nor Nature nor God. All concepts that humanity has inherited and fabricated return from that mystery, finding nothing there, except its beckoning, a beckoning which no concern of man can resist or ignore, for brings it to rest all his passions and all his unrest. As for his daily life, that too is a marvel, a miracle, miracle the absolute with no qualifications, a hint of which the reader will find in the brief life-sketch of the Founder of Smat āvāda given below. When the seeker has received the Grace Abounding flowing out of the presence of a sage, he will prepare himself to follow the latter’s way to redemption, becoming ripe for the hard discipline awaiting him.

That last discipline is simaran, remembrance, remembrance of the Name, the process of meditation that implies one’s stepping back from one’s senses, from one’s manas, mind that thinks of things in terms of desirable or undesirable, in terms of seeking and aversion, and from buddhi, the faculty that determinates phenomena, puts limits to them as against each other. Stepping back from these constituents of his being, the seeker of the truth lives as breath, as only breath until a moment comes when he steps back from the motion of his breath too to turn a nonmoving witness of its motion. That is the moment when he comes to be aware of his being the interior, the most interior, beyond the ken of his thinking and his intellect. His soul already subdued and chastened, he in peace and humility, surrenders himself unto that mystery within, mystery that would never consent to be phenomenalised. All innocence, this humble pilgrim to being then self-submits to that mystery to die into it. It is then, only then that he comes to be saved, in this his self-sacrifice, in this his self-extinction. Self-hood is all misery, all pain and all tragedy, it is all evil and all sinful; in its cessation alone lies our salvation, our redemption and our liberation. That is the truth, which we must pay heed to in this age where everyone is taught to nurture this selfhood, to augment it and revere it. This civilisation, Samtavad would warn in unambiguous terms, is civlisation the suicidal, an invitation to the fury of an unprecedented nemesis if humanity does not put a check to its lust for knowledge and power and the naked consumer culture that this lust has generated and will generate. No peace will come to the world if this civilisation does not wake up to the call of the beyond and does not direct its mind inwards to investigate the Life within. Investigation of the material world should be kept within limits; it should never be resorted to at the cost of investigation of the Spirit within. If this civilisation persists with its outward obsession then nothing can save it from ruin, ruin complete and total.

A Word about the founder of Samatavada :

Acknowledgement :

Quite a few sentences here have been taken from the Preface to the English Version of the Samat āvilāsa (in Press) with the consent of the Translator and the Publishers.